Ireland. Vacancies, expensive rents and slumlords are driving more and more people into homelessness. Dublin is particularly affected. This summer, various grassroots initiatives began to defend themselves and draw attention to the housing crisis. The background to a summer of occupations.

Wiliam Murphy, photographer from Dublin, lived in San Jose, California, in 1979 when he visited San Franscico on a weekend and witnessed homelessness on the streets for the first time in his life.

For him – shocking and unusual, because in 1970 it was customary for the Irish state to guarantee people a roof over their heads. Many of his colleagues lived in Cremlin, Bellyfermon and Cabra. This was to change, however, when the state handed over the construction and maintenance of social housing to the private sector.

After his return to Dublin: Discovering the homelessness

It was in 2007, after his return to Dublin. He began to notice the increasing number of people sleeping ruff. In front of the shops in the city centre and elsewhere. Back then he fell on tears at his workplace because his colleagues either didn’t believe him or claimed they were drug addicts.

But since then the problem has worsened. To a point where it is no longer possible to talk down the problem of homelessness.

Thanks to his experience abroad, Murphy has found parallels with the housing situation between San-Franscico and Dublin. Both being cities which aren’t affordable for the working-class.

The current homelessness problem leaves him with a bitter aftertaste. Especially since he himself was affected five years ago and had to fight to pay off his mortgage on his apartment. Murphy archives the streets of today’s Dublin with his camera.

Observing the looming housing crisis

When I was in Dublin at the beginning of July last year, some situations caught my attention:

On the one hand, the many tourists and language students who led an exuberant life between learning English and bar hopping. And on the other hand the high number of homeless and homeless people, who stood in contrast to the huge number of empty and barricaded houses.

According to the Focus Ireland charity and government surveys, the number of homeless people in Ireland in 2014 was just under 4,000, rising to almost 10,000 in four years. Individuals and families in private tenancies suffer. In October (2018), 1700 families, including 3725 children, went to emergency shelter.

But the number of unreported cases is probably much higher. Many people get caught up in their social network of friends and acquaintances (- couch surfing). However, these cases are not recorded in the statistics.

The housing shortage has steadily worsened since the economic crisis in 2008. Among other things for the purpose of the legislative decision to cut funds for social housing between the crisis and 2014 by 72% and to bet on private landlords. As a result, the budget fell from 1.34 billion to 390 million euros.

A paradox of Dublin’s real estate – No affordable apartments despite rampant vacancies

In 2015, the Dublin Inquierer produced a first incomplete map of empty buildings. This already included a number of 389 units.

The vacancy is easy to see – between the barricaded windows, decaying facades and high barriers of these buildings. The following year, when the Housing Agency published a vacancy report for Dublin, 38,000 vacant properties were listed. Since then, according to TheGuardian, the number has fallen to 30,000 vacant properties by 2018. Yet the number of homeless people has increased. Which is why, people have to sleep on the streets despite such a large amount of unused residential space.

Grassroot initiatives organizing the resistance against Irish housing madness

However, the affected citizens do not admit defeat and begin to point out the grievance by creative methods. The Irish Housing Network (IHN), for example, called in the summer, for vacancies throughout Ireland to be marked with yellow posters. On a yellow background, the outline of a family under a roof is displayed and joined by the sentence: “Shame on you – this could be a home“.

The problem of vacant buildings, which are either in very poor condition and have been waiting for years for a new development or remain unused for speculative reasons, characterizes the urban landscape. Dublin, with its high rents, is lucrative for real estate sharks, who are driven up by vacancies.

Providers such as AirBnB also take Irish housing away. As the owners, in addition to a high profit margin, do not have to adhere to the classic tenancy law. Dublin, as a university and language school city, is particularly affected. But the 1300 holiday apartments and 1100 rooms listed by InsideAirBnB are only the tip of the iceberg.

In the clutches of Irish Slumlords.

Particularly bad landlords are known in linguistic usage as slumlords. They are the Irish version of the French “Marchands de sommeil”. These rental sharks rent rooms with six to eight beds for up to 450 Euros per capita. Mostly this concerns people in precarious situations who do not have the possibility to defend themselves. These overcrowded sleeping quarters are not maintained by the slumlords. Fire protection deficiencies and mould on the walls are part of their everyday lives.

Those who end up in such dubious tenancies rarely receive the prescribed rental book. In this the personal data of the owner must be noted, as well as a listing of the past rent prices show. It is intended to protect tenants from arbitrariness. But in the absence of rigorous implementation, this rule is disregarded in many cases. Those affected find themselves in a dilemma. Because they depend on accommodation, they do not always have the means to assert their rights.

A small Twitter survey conducted by the Dublin Central Housing Action, which supports people in housing need and is part of the TBTC Dublin (“Take Back The City Dublin”) movement, found out that 87% of 650 respondents had not received a rental book:

Determined to face rental sharks and defend tenants

Slumleaks a collective of affected people has come together under the motif: “Exposing Irish Slumlords” and reports regularly on harassment, threats of violence and expulsions by unscrupulous slumlords. The case Paul Howard Tenant#1 gives insights into the mundane life of the rental shark Paul Howard:

Every month we collect our rent and Paul Howard or one of his friends comes by to collect it – altogether 4200 € in cash..

An affected tenant at Mountjoy Square about the payment of the rent

The six tenants at Mountjoy Square in Dublin 1 found themselves suddenly on the street at the end of last year. Expelled from their apartment on 13 December and nowhere to go. The owner had changed the lock on the front door and put all their belongings in plastic bags on the street. Previously they had gone to court against their landlord. The state of the apartment, with a broken window and mold on the walls being depictable. But as well a preceding arbitrary rent increase from 650 to 750 Euros, had become too much for the former tenants. The eviction, which took place in winter, is considered illegal by Slumleaks.

Dublin’s Housing networks answering the crisis

Direct Action Methods for empowering the rights of tenants

The activists of the grassroots movements use direct action methods to draw attention to the deplorable conditions. Posters and banner campaigns, food distribution and temporary occupations belong to the activities of the militants. Direct action, which can also be understood as a synonym for civil disobedience, describes the possibilities of using pacifist approaches to point out social problems and initiate public debate. As in the case of “Take Trinity Back,” a student protest that broke out in March 2018:

The Trinity College board had intended to introduce additional costs of 450 euros for retaking exams. This was followed by students protesting and occupying the historic “Dinning Hall” for three days. When the occupation was dissolved, 1000 students came and cheered on their fellow students. The university management struck a conciliatory note and let go of his plan. The occupation of the university building represented the first breeze which would spread to the streets of Dublin. Spring was over, but things were already boiling at other places…

The beginning of a summer of occupations

May. A few blocks from Mountjoy Square: The residents of five houses in Summerhill Parade 33-39, Dublin 1, were evicted from their rooms. These, who shared the accommodation with up to twenty other tenants per house and are to a large extent of Brazilian origin, were unable to name the owner of the houses in an interview with the Irish Times. The residents were supported by various grassroots initiatives including the Dublin Central Housing Action, Take back Trinity, Brazilian Left Front and four other local movements.

August 7th – In protest, the groups begin to occupy Summerhill Parade 35 and draw attention to the local housing problems.

For months now, the Dublin Central Housing Action has been organizing a Facebook campaign against Pat’ODonnel. This and his investment fund, the “Co Ltd Retirement and Death Benefit Plan” – a pension fund of 67 members. At the beginning of August, a spokesman told the Irish Times that the O’Donnels did not own the properties in the Summerhill Parade. However, in mid-August, Pat’ODonnel filed a lawsuit against the occupiers on behalf of his pension fund.

In the video the squat is officially declared, as one of the activists gives a speech about the situation of the people and demands a purchase right of the city on Pat O’Donnel’s house.

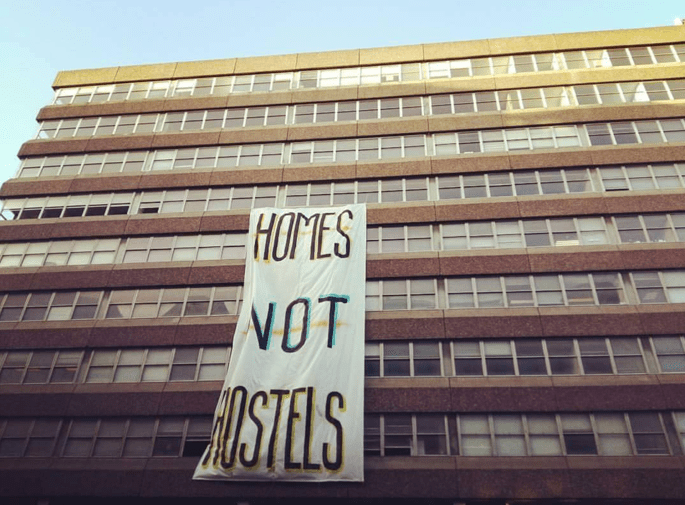

The words are not heard and ten days later the activists leave the building in a demonstration, marching with a banner: “Build homes, not profits“.

August 17 – The court decided to evict them. 750 metres and a few bends further, the activists from Take back the City (TBTCDublin) marched into a vacant house on Frederick Street North 34, owned by an insurance company and standing empty for three years.

25 August – On the occasion of Pope Francis’s visit to Dublin, activists proclaim a Saturday of action in which the house is occupied exclusively by women and children. The activists see this as a reminder of the fact that single parents and their pupils had to do forced labour in the Magdalenen laundries until the late 20th century. A national trauma for which the Irish state apologised to over 10,000 people as late as in 2013.

After 25 days – Facing the eviction but standing the ground

11 September – Two weeks earlier, the court had once again ruled in favour of the landlords. But the house remained occupied. More and more people started supporting TBTCDublin.

Suddenly that Tuesday evening at about seven o’clock, a sprinter with no numberplate on the front appeared and masked persons emerged. The privat hired contractors tried to gain access to the house and only calmed down when the local police arrived and took over.

Five of the activists were brought to the police station on Store Street in a rabid manner. According to the newspaper Thejournal, which reported in detail about the eviction, up to 100 demonstrators gathered in front of the house. Later, the demonstration moved outside the police station, whereupon three of the activists were released. Nevertheless, the house project was ended.

In solidarity with TBTCDublin, squatting took place throughout Ireland, such as in Waterford, where activists held a 24-hour occupation of an empty building in the city.

This article was actualized the 05.03.2020